Theme: Reconciliation. In what way?

Saturday July 6th. 2019, Christus Triumfator church, The Hague.

The conference was made possible thanks to a donation of the National Comittee 4 and 5 May.  Program:

Program:

- Welcome – Janneke Roos

- Opening – Yukari Tangena – Suzuki

- Can what once separated us also connect us? – Philip de Heer

- My encounter of “comfort women” for reconciliation – Eriko Ikeda

- Q&A – Janneke Roos

- Study of Reconciliation – Prof. Toyomi Asano

- Sharing History – Maarten Hidskes

- Q&A – Janneke Roos

- Explanation of the artwork Who is the Dalang ? Who are the Dalangs? – Arletta Kaper

- Dialogue in small groups

- Feed back of group dialogues.

- Closing words – Prof. Takamitsu Muraoka

1. Welcome ⎮Janneke Roos

Welcome on behalf of the Foundation Dialogue NJI

2. Opening Speech⎮Yukari Tangena – Suzuki

Good morning, my friends, ladies and gentlemen, I am Yukari Tangena-Suzuki. On behalf of the board members of the Stichting Dialoog Nederland-Japan-Indonesie I would like to welcome you all to the 21st Dialogue NJI Conference. I am very pleased and honored to have you here.

“Reconciliation, In What Way?” This is the theme we have today and I will try to explain what our intention with this theme is. After the war ended, the struggle, anger or despair of people did not disappear although it seemed like that, since most people did not talk about it. This happened here in the Netherlands but also in Japan and Indonesia. Those who perpetrated the horrible killing actions or their victims, or those who had to survive in Japanese, or Siberian Camps hid their memories and kept their mouth shut. Memories are gradually fading but never disappear. I still remember a good friend of mine who was interned in a Japanese camp. He seemed to have overcome the problems, but he told me once, that70 years after the war, after undergoing an operation under anesthesia, he had terrifying nightmares of the war. Since then he was always afraid to have a surgery again.

At our conference we always listened to the precious stories of the first generation. But this conference is the first time after 20 conferences since 2000 that we have only speakers of the second generation. Some of you might find it strange to talk about reconciliation and the second generation who has not experienced any wars. But as I said earlier the memories of their parents or grandparents were always there since they were born, no matter whether they spoke about these or not. Children unconsciously grew up with the memories of their parents. All board members, including myself are from the second generation. We wanted to rephrase what it is, to seek reconciliation for the second and the following generations. With these thoughts we chose the theme “Reconciliation: in what way?” for this conference and selected the honorable speakers.

Even though there is still a demonstration in front of the Japanese Embassy every month, in the Netherlands the issues of the Indonesian Independence War are far more topical at this moment than those of WW2. So now we are confronted with problems from after two wars, not only after World War 2 but also after the Indonesian Independence War.

We have always taken some distance from political affairs and looked for grassroots reconciliation of citizens. But when we look around the world today we still find self-centered politicians who seem to have learned nothing from our past. This also means that there is still a large number of voters who did not learn anything from the past. Ladies and gentlemen, we must stay alert. Nowadays, as we all know, religion, that used to set norms and values, has less and less influence on people. So if there are no norms and values how should young generations learn from history? I believe we must learn from history that each one of us is responsible for peace building. In our history text books it is quite common that we are taught that we are victims and far less that we were also aggressors. Prof. Carol Gluck of Colombia University even dares to say that history text books of each country are nothing but “collective memories”. She clearly makes a distinction between history and collective memories. I think it is especially important for young people to learn also about the history of aggression of their own country. We must be open about this, because I believe that it is absolutely necessary for children to learn to feel the pain caused by us to others. It is so precious to learn to be sensitive about this. After all everything starts from feeling the pain of victims that you caused directly or indirectly. Feeling their pain is most essential to remind yourself that you are also responsible to build peace. If you focus only on your identity as a victim and have no eye for your role as an aggressor I don’t think you can work for the future because you would only be looking at your own anger and pain. Once you feel the pain you caused you are able to become a peace builder.

About a week ago the National Museum of Sofiahof was officially opened. The theme of their first exhibition is “Fight for Freedom”. I was very impressed by this theme and the first panel which explained the exhibition. Maybe most of the Dutch visitors would not have noticed, but this is very unique! If it would have been an ordinary exhibition, like in the past, the theme would have been “Fight for OUR freedom”. Such a theme would have been quite normal here. I quote the panel, “Fight for Freedom: many faces of resistance: Invasion, resistance, freedom have different meanings according to each person. What freedom means to you is determined by your situation and your ideal“. I am actually very astonished to read this because here I suddenly see the acceptance of existence of different perspectives on invasion, resistance and freedom. Don’t you also think these words are worth considering more deeply?

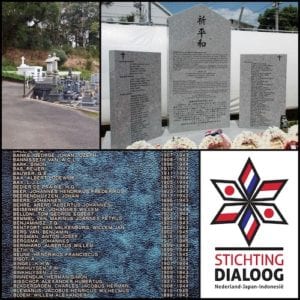

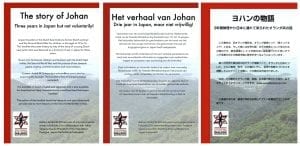

Ladies and gentlemen, now, I would like to introduce one of our activities the Stichting Dialoog Nederland-Japan-Indonesie carried out last year. Some of you might still remember that five years ago we collected money for building a monument for P.O.W. camp Fukuoka No.2. Henk Kleijn who is a survivor of this camp is also present today. As a byproduct of that monument, a project for a booklet to support teaching history was started. Here I have three booklets. I said three booklets but the contents are all identical but in three languages. Dutch, English and Japanese. This booklet was written by Andre Schram, advisor of our Dialoog NJI. As a main character in the booklet he uses his father who was interned in P.O.W. Camp Fukuoka No.2.

Ladies and gentlemen, now, I would like to introduce one of our activities the Stichting Dialoog Nederland-Japan-Indonesie carried out last year. Some of you might still remember that five years ago we collected money for building a monument for P.O.W. camp Fukuoka No.2. Henk Kleijn who is a survivor of this camp is also present today. As a byproduct of that monument, a project for a booklet to support teaching history was started. Here I have three booklets. I said three booklets but the contents are all identical but in three languages. Dutch, English and Japanese. This booklet was written by Andre Schram, advisor of our Dialoog NJI. As a main character in the booklet he uses his father who was interned in P.O.W. Camp Fukuoka No.2.  But the booklet also describes how Japanese people were suffering outside of this camp in Koyagi, Nagasaki. This part was written based on interviews of elderly people of the town of Koyagi done by Koyagi Junior High School pupils. Their school is built on the site of the Camp and of the monument. We are very proud that these text booklets tell not only the pain of Andre’s father and his comrades but also the pain of the other side. We are so pleased that these text booklets are used in the classrooms of both the Netherlands and japan. As you can imagine this kind of project touches very delicate issues. I said earlier that we both know only our collective memories. If we can only send a message that “you, the other side” are wrong, we end up with conflicts, because we have nothing to share with each-other. But once you feel the pain on the other side something positive happens. At the end of this booklet André wrote “Even though you live in a part of the world where war seems highly improbable, it might become reality if we don’t learn from the past!”. On the monument built by Nagasaki citizens, words of their remorse and apology are engraved, so they realize they are not only victims, but also aggressors.

But the booklet also describes how Japanese people were suffering outside of this camp in Koyagi, Nagasaki. This part was written based on interviews of elderly people of the town of Koyagi done by Koyagi Junior High School pupils. Their school is built on the site of the Camp and of the monument. We are very proud that these text booklets tell not only the pain of Andre’s father and his comrades but also the pain of the other side. We are so pleased that these text booklets are used in the classrooms of both the Netherlands and japan. As you can imagine this kind of project touches very delicate issues. I said earlier that we both know only our collective memories. If we can only send a message that “you, the other side” are wrong, we end up with conflicts, because we have nothing to share with each-other. But once you feel the pain on the other side something positive happens. At the end of this booklet André wrote “Even though you live in a part of the world where war seems highly improbable, it might become reality if we don’t learn from the past!”. On the monument built by Nagasaki citizens, words of their remorse and apology are engraved, so they realize they are not only victims, but also aggressors.

This project has developed further with an excellent TV report of NHK(Japanese BBC). All 500 Japanese booklets are gone and are being reprinted again. But this booklet-project is not yet complete until the perspective of the Indonesians is included. We hope also to publish a booklet which can be used in classrooms in the Netherlands and Indonesia. And through this project and all other projects we strive for our next generation to learn the many perspectives of the past so that it will give the second and the following generations their new identity.

I would like to thank you all for your attention and I wish you a very fruitful dialogue today.

3. “Can what once separated us”, also connect us? ⎮Philip de Heer

Philip de Heer

Come tonight with stories

How the war has disappeared

Recount them hundredfold

I will cry with every story told

These are the last four lines of the poem entitled PEACE by Leo Vroman. He wrote this poem in 1954. When one takes the trouble to read the piece in its entirety, one will notice that it contains more than abstract poetic impressions. Whoever reads about the harsh realities of his life, will learn that he fled from Holland in the early days of the war. He managed to reach England, travelled on to Indonesia, where before long the war caught up with him. After having been interned in various camps in the archipelago, he ended up by being transported to Japan where he performed forced labour till the war was over.

The number of people who like the poet speak about personal experiences from the time in question, inevitably becomes smaller. Even if you include the Indonesian War of Independence, this particular period of violence and human suffering had ended before I was born. Therefore it is important to state from the beginning that I address you today as somebody who talks about other people’s stories. I did not suffer, nobody has been unjust to me. Consequently the term “ reconciliation “ takes a complete different meaning in my mouth.

Our grandparents, our parents, and probably even some of you, have lived  through ordeals of which we can only fervently hope that they will not afflict us as they did them. The negative experiences they encountered were too pervasive to wish them away with mantras like: time heals all wounds, to forgive is to forget, one should place one’s private pains in a broader historical contexts. In retrospect it is actually a miracle that people are able to handle such harrowing experiences in a way that makes it possible for them to continue living their scarred existences. It is a well known fact that for some victims that has been a life long, uphill struggle. Comforting help in the form of a dialogue with other victims, with persons from the “ perpetrator”- countries with their fair share of victims of their own, and the heroic efforts to reach some form of reconciliation, can therefore not be praised enough.

through ordeals of which we can only fervently hope that they will not afflict us as they did them. The negative experiences they encountered were too pervasive to wish them away with mantras like: time heals all wounds, to forgive is to forget, one should place one’s private pains in a broader historical contexts. In retrospect it is actually a miracle that people are able to handle such harrowing experiences in a way that makes it possible for them to continue living their scarred existences. It is a well known fact that for some victims that has been a life long, uphill struggle. Comforting help in the form of a dialogue with other victims, with persons from the “ perpetrator”- countries with their fair share of victims of their own, and the heroic efforts to reach some form of reconciliation, can therefore not be praised enough.

Seventy years after the events, my generation is one that can look at that past in a different manner. Unburdened by personal suffering and emotions, we actually are in a position to lift up the facts of those years from the strict personal and place them in that broader historical context that undoubtedly and objectively exists. By doing so we render these facts more durable. I am a firm believer in the theory that history does provide us with lessons for the future. But that demands that we seriously try to look at the past with an eye for all its facets, at all its sides. That presupposes that we abandon “idees fixes “. Such an attitude is easier to embrace for those without traumas that the former generation always carries with it. Perhaps we will even manage in that process to help the older generation to accept the “ why me o, Lord”- aspect of their war, or at least help them to understand the irrationality of Fate. Better knowledge will undoubtedly help us to see the warning signals earlier, so that we may help to avoid similar disasters in the future.

The organizers were so kind to ask me to address you today because my family history provides a number of links to the questions about the why and how of the violent confrontation in the years 1942-1949. Reconciliation starts with a better understanding of the motives of the other. That is, for to be crystal clear, something else than justifying the comfort women-scandal, the massacre of Indos and Chinese Indonesians during the bersiap-period or the 100.000 Indonesian victims of Dutch military interventions after 1945.

My great-grandfather was a member of the all-European Colonial Civil Service. In that capacity he worked in Western Sumatra and on Borneo in the last quarter of the 19th century. He had married a Japanese woman who he had met during a leave of absence to Singapore. After his retirement the couple moved to Nagasaki from which town my great-grandmother hailed. They had five children of which my grandfather was the eldest.

My great-grandfather was a member of the all-European Colonial Civil Service. In that capacity he worked in Western Sumatra and on Borneo in the last quarter of the 19th century. He had married a Japanese woman who he had met during a leave of absence to Singapore. After his retirement the couple moved to Nagasaki from which town my great-grandmother hailed. They had five children of which my grandfather was the eldest.

To the memories of his childhood in Japan belonged the Russian prisoners of Russo-Japanese war of 905-1907 who were interned in Nagasaki. They were on the whole treated well. Russian POWs, for example that died during their captivity, were respectfully buried in the Dutch cemetery where once the dead of Deshima had been laid to rest. This kind of treatment was in sharp contrast to Japanese behaviour during the war with China, a decade earlier. Ruthless behaviour against defenseless Chinese civilians shocked international public opinion to the extent that the Western Powers felt it necessary to force Japan to give up its conquests in Southern Manchuria. The government in Tokyo was obviously aware of this during the second international conflict in modern Japanese history and behaved accordingly. It was rewarded: with Port Arthur as the spoils of victory.

Thirty years later the approach was different again. In 1937 Japanese diplomats stationed in Nanking reminded their superiors at Gaimusho of Japan’s obligations under the Geneva Conventions on Humanitarian Conduct of War. Even though Japan had not ratified these treaties, signatories, of which Japan was one, were expected to act in accordance with, if not the letter, than at least the spirit of these conventions, they reminded their superiors. This, the Japanese armies that had taken Nanking, decidedly did not, according to their opinion. Their warnings were not heeded. During the Tokyo Tribunal the Minister of Foreign Affairs of the time, Togo, paid the price. He was convicted for war crimes. With the knowledge he had of what had happened, he should have resigned in protest.

Another consequence of the outcome of the Russo-Japanese War was wave of virulent nationalism. This resulted in the interdiction of languages other than Japanese as a medium of instruction. This applied also to the international school of Nagasaki: Kaiseki Gakko, which my grandfather attended. With an eye on the education of his children, the family decided to move back to Indonesia. From distancing and isolating yourself from the other to feelings of superiority and even xenophobia, is only a short step. It rarely bodes well.

I quickly move forward in time to Spring 1942. The war in Europe was in full swing and had just started in earnest in South East-Asia. The De Heer-family was hit by it too.

-The eldest son, my father studying in Delft, had been drafted into the army and stationed near airport Iepenburg during the mobilization. Iepenburg had been a site of fierce fighting in the early days of the war. In Batavia his parents did not now how he had fared.

-After Pearl Harbour it had obviously been just a matter of time before Indonesia would be attacked. When that finally happened, my Japanese great-grandmother Yamaguchi refused food and drink and died after a few days. She could not bear the shame of her countrymen invading her new fatherland.

-My grandfather, censor, interpreter and decoder working at the Netherlands East-Indies Intelligence Service(NEFIS) and his youngest son who had been drafted into the army, became POWs. The occupier quickly became aware of my grandfathers skills and with the permission of his commanding officer, he was allowed to leave the POW camp. To his former superiors it seemed a good idea to have a man of their own at interrogations, hoping that there would be less misunderstanding! The organization my grandfather was assigned to was, however, the notorious Kempeitai.

-After a while the Japanese learned about his son and suggested that he could join his father and work alongside him. My grandfather turned the offer down with the argument that my uncle had no specific skills that would justify such preferential treatment. Working for the Japanese would, in his case, have been desertion and treason. He was told that in that case my uncle would be deported to Japan and put to work in a coalmine near Nagasaki, to ensure the loyal cooperation of my grandfather.

My grandfather never told anyone anything about what he had seen, heard or witnessed. Even though I was rather close to him, he did not bring up the war period. I did not ask him about it either, strangely enough. He was my tutor for Japanese language and history during my studies and there had been plenty of opportunities, on both sides, to shed some light on that period of his life. Only this one story came up: my grandfather recounted how he had been struck by the fact how brutally Japanese recruits were treated by all higher in seniority or rank. The entire first year in the army they would be slapped in the face by every one that had served longer. The consequence was painfully swollen faces. These thus brutalized young men were unlikely to have had much empathy for defeated, white prisoners. Homo homini lupus is a false statement; – man is not like a wolf in relation to other human beings. Nevertheless, it is obviously all too easy to turn a normal person into a vicious dog.

Not being interned, my grandfather witnessed the rise of a new nation. The inhabitants of this fledgling country to be, will probably have realized that, propaganda notwithstanding, the Asian liberators did not have the intention to hand their newly acquired territories to their inhabitants soon. Mismanagement, in particular of the food supplies, and endemic violence resulted in local confrontations of the native population and their new masters. My grandfather once was ordered to accompany a Japanese detachment during a pacification campaign somewhere in West-Java. However because of a severe attack of dysentery he had remained at home. He was lucky, of the Japanese soldiers hat went out, none came back.

We all know how the war ended. The target for the first atomic bomb had been carefully selected; Hiroshima had been the centre of the Japanese military and base of operations for Japanese imperialism since 1894. Failing an adequate Japanese response, it was decided to drop a second bomb on Fukuoka. Bad weather and cloud cover made that the planes were diverted to a reserve target: Nagasaki and its navy shipyards. These, however, were hardly damaged. Neither were Deshima and the former International Settlement full of wooden houses where my grandfather grew up. Hardest hit was the civilian population of the upper reaches of the town. The fact that American soldiers close to the site of the detonation of the first atomic bomb, received protective gear in the form of sun glasses only and the fact that two weeks after the end of the war, weakened, former POWs, including my uncle, were evacuated though the radiation rich port, shows to my opinion that all the ramifications of the use of this new weapon had not been thought through. But the bombs certainly led to the end of hostilities.

My grandfather was deployed as an interpreter at the war crimes tribunal at Pontianac in Borneo. Once again he kept his knowledge and impressions to himself. Curiously, all I know about it came from copies of court protocols that I found in the library of my residence in Tokyo. During our discussions on Japanese history, he only mentioned in passing how much he had been struck by the fact that Japanese officers did not shirk their responsibility and in general acknowledged the crimes with which they were charged. Here no: wir haben es nicht gewusst!

Thanks to the findings of this court and similar war crimes tribunals in the archipelago, the scale of the “comfort women” phenomenon was revealed. Thanks to Dutch insistence on this particularly heinous crime, this atrocity was added to the list of crimes the Tokyo Tribunal addressed.

In the administration of justice regarding crimes committed during the war, one cannot escape the impression that the sufferings of the Europeans took central stage. Relatively speaking, less attention is given to the behaviour of the occupier with regard to the indigenous population. The rude treatment of the romusha, in particular those serving outside Indonesia, was such that the death rate outstripped that of allied POWs.

The Chinese, in pre-war Indonesia categorized as Foreign Orientals, were regarded by the Japanese with great suspicion. They assumed that they harbored pro-Allied sentiments, since Chiang Kaishek fought alongside the British and the Americans. The Japanese authorities did little to discourage the traditional anti-Chinese feelings amongst the general population.

Anyone looking at the finding of these special courts and comparing them to the conclusions with justice meted out in Holland, cannot but note that in Europe death sentences was seldom handed down. Just the NSB-top leadership and a few particularly notorious concentration-camp commanders were executed. The juridical decisions of the war crimes tribunals in the East counted more than 220 death sentences. Now seventy years later, one has the impressions that vindictiveness played a role. Were at the time the eyes of Justice, who had to adjudicate the humiliations the Europeans had to suffer from the hands of Asians, sufficiently blindfolded?

Small wonder that, against this background of dormant indigenous violence, anti-Western and anti-Chinese sentiments, the tensions over the future of the country erupted in a murderous mood in the vacuum created by the Japanese capitulation. It was directed in the first instance against the Europeans who had left the camps, but in equal measure against the Indos whose loyalty to the new Indonesia the republicans questioned and against the traditional scapegoats: the Chinese.

Why did the bersiap-violence gain so much traction? Was it triggered by the looming threat of restored belanda-rule? Or was the enzyme the collective memory of four centuries of occupation, suppression, and exploitation that caused this orgy of blood and violence. The subsequent Dutch attempts to restore, if need be with brute force, colonial rule can never be justified by referring to the bersiap-violence. But to organize bands of armed young men in times of political instability, has led in the forties, and in the sixties as well as in the nineties of the last century to mass-killings of Indonesians of Chinese descent. The historical lessons our Indonesian interlocutors could draw from these social eruptions is that once strong-arm boys enter the scene, it inevitably bodes very much ill for minorities and dissenters.

My grandparents left Indonesia shortly after the duties in Pontianac had ended, never to return. The role my grandfather had played in the trials of Japanese with many friends and sympathizers in republican circles, rendered staying impossible. With their demobilized son they left for Holland. Granddad picked up his duties at the Navy Intelligence Services in Amsterdam , my uncle Koen went to Leiden to study Indonesian languages.

My grandparents never spoke about Japanese or Indonesians in a reproachful or condescending manner, although the former had overturned their lives completely and the latter had taken away their ”Land van Herkomst“. My parents who lost two children during the war, never turned their private grief into resentment against all German individuals. “Krauts” and “ Japs”, were words never used in my family; with a 100% Japanese great-grandmother and both my sisters married to Germans, it would have sounded both wrong and unkind.

Historically speaking, the Dutch came to Indonesia very early and left obviously too late. The Japanese presence there was short, intense and above all violent. What remained unchanged is what had always been there: the Indonesian archipelago and its inhabitants. The confrontation between the Japanese and the Dutch lasted less than 5 years. With the passing away of those from these two outsider-countries whom witnessed it all in person, the memories of this confrontation and the direct pain it caused, will fade away. What remains is the general history of a human tragedy out of which suddenly grew present day Indonesia. This is not an easy legacy for that country. But that is usually the case when you inherit something: you have to accept both the pros and cons. To write the history of the birth of Indonesia together with the other passers-by that played their role in it, seems to me the way forward with our three-sided reconciliation-dialogue. I think that my generation, both in Holland and in Japan, is by now done with that short and unhappy common history in a country in which actually both of us had no natural right or reason to be. Let us from now on help the rightful owners of the place to turn our common heritage into a correct and informative chapter of their national history.

4. Encounter between a Japanese woman and victims of sexual slavery, and reconciliation

⎮Eriko Ikeda

Eriko Ikeda (Honorary director ofWAM, Women’s Active Museum, Tokyo).

1. Introduction

Over the 15 years since the start of Japan’s invasion of China, the Japanese Army set up comfort stations in many colonies and occupied territories, and exploited an enormous number of women there as sexual slaves. Only in the 90’s of the last century, nearly half a century after Japan’s defeat, the issue surfaced when a few victims came forward. Nowadays the situation is known almost in its entirety.

But the Japanese Government headed by Premier Abe would not only not admit Japan’s responsibility in this matter, but also has been trying to conceal the damages and to deny the historicity of the exploitation itself. Just as in the era of the Imperial Japan this Government is attempting to manipulate the education and mass media. Such a stance has been severely criticised by the victimised nations and the issue of “comfort women” has been left unresolved, and 70 years after the end of the War “reconciliation” is still far away.

The resolution of the “comfort women” issue is possible only when the perpetrators and the victims reach a common understanding of the history and the two parties face each other for a dialogue. Furthermore, the Government of Japan is obliged to admit its legal responsibility, to offer victims sincere apologies and to pay compensations for the damages caused, and to endeavour to retain these historical facts for perpetual memory. However, we Japanese citizens live under the political leadership which refuses to face the issue of “comfort women.” We have to strive to find out how to meet the responsibility and guilt arising from our last war and what we can do towards the resolution of the issue and “reconciliation”.

The resolution of the “comfort women” issue is possible only when the perpetrators and the victims reach a common understanding of the history and the two parties face each other for a dialogue. Furthermore, the Government of Japan is obliged to admit its legal responsibility, to offer victims sincere apologies and to pay compensations for the damages caused, and to endeavour to retain these historical facts for perpetual memory. However, we Japanese citizens live under the political leadership which refuses to face the issue of “comfort women.” We have to strive to find out how to meet the responsibility and guilt arising from our last war and what we can do towards the resolution of the issue and “reconciliation”.

For 37 years until I retired in 2010 I was involved in the production of various projects of the NHK, a Japanese equivalent of BBC. When I directed the production of a programme over “comfort women”, I came into contact with citizens’ organisations supporting “comfort women”. For the past 20 years I have been involved in the production of a documentary film on “comfort women”, supported legal cases on behalf of “comfort women”, and also in the organisation of the women’s international court held in 2000. In 2005 WAM was established to carry on the spirit of the Women’s International Court, and I am still involved in its running.

the production of a programme over “comfort women”, I came into contact with citizens’ organisations supporting “comfort women”. For the past 20 years I have been involved in the production of a documentary film on “comfort women”, supported legal cases on behalf of “comfort women”, and also in the organisation of the women’s international court held in 2000. In 2005 WAM was established to carry on the spirit of the Women’s International Court, and I am still involved in its running.

My father was stationed in China as a soldier of the Japanese Imperial Army and my mother survived the bombardment of Tokyo on 10 March 1945. I grew up, hearing from my parents about their wartime experiences. As a high-school student I read Anne Frank’s Diary, and through media reports on the Vietnam War I began to think about the issue of fascism and war. Eventually I decided to reform the Japanese mass media from inside and found employment with the NHK. Investigating social issues relating to women, human rights, education, and discrimination I got involved in the production of programmes dealing with the bombardment of Tokyo, the atomic bombs, school children sent away to the countryside, Japanese children left in China, the colonisation of Manchuria and the like, all relating to the Pacific War. Initially I was mainly interested in the damages suffered by the Japanese. But in the late 80’s some of our audience asked us “Why aren’t we told about the damages suffered by victims in Asia?” I consulted and discussed the matter with my colleagues. Though we had to fight the stance taken by the top management of the NHK, we began to deal with war crimes committed by the Japanese Army.

Since 1990 NHK war programmes began to deal seriously with damages brought about by the Japanese Army. Some of the programmes were positively evaluated. None the less, the issue of “comfort women” was still a taboo, and the mass media kept away from it. Why so? I would like to share with you now how this issue has become my life work, how the issue has been dealt with in Japan, Japan’s reconciliation with Asian countries and how I face the issue of ‘reconciliation.’

2. The issue of “comfort women” kept in secret and the coming out of victims

During the Pacific War the Japanese Army set up comfort stations for the prevention of rapes by its soldiers and the prevention of venereal diseases. However, its media coverage was strictly forbidden, and “comfort women” were viewed as wartime prostitutes. Many Japanese women who were working in brothels or had been sold away because of the poverty of their families were also dispatched to comfort stations in Japan and overseas. These data were not only covered up, but with Japan’s defeat the military top feared that the issue might come up in a postwar military tribunal and ordered all the relevant documents to be burned and destroyed. A large quantity of relevant data was lost for ever.

Shortly after the end of the war the Japanese Government sent a directive to all regional governments to have comfort stations built for troops of the Occupation Forces near their military bases. The advertisement “New women sought” attracted about 70,000 women. All this was done in secret. “Comfort women” are soldiers’ “necessities”. But that policy advocated and executed by the Government was not made public, a policy maintained both during the Pacific War and thereafter.

Shortly after the end of the war the Japanese Government sent a directive to all regional governments to have comfort stations built for troops of the Occupation Forces near their military bases. The advertisement “New women sought” attracted about 70,000 women. All this was done in secret. “Comfort women” are soldiers’ “necessities”. But that policy advocated and executed by the Government was not made public, a policy maintained both during the Pacific War and thereafter.

In 1970’s, rapes and atrocities committed by American soldiers during the Vietnam war were reported and anti-war movements began to spread worldwide. Only then, for the first time after the war, Japanese war veterans began to face war crimes committed during the Pacific War. Autobiographies of former Japanese “comfort women” and non-fiction works were published, the presence of former Korean “comfort women” still living in Okinawa became known, and the issue of “comfort women” was also taken up in the women’s liberation movement.

However, in 1991, when Ms Kim Haksun came out as a former “comfort woman.” Then the issue of “comfort women” began to be viewed as a denigration of women’s human dignity and a grave war crime. Ms Kim was followed by a large number of victims in other Asian countries. They took the matter to Japanese courts and demanded the official apology by the Japanese Government and financial compensation. However all the ten civil cases were thrown out by the Supreme Court of Japan. In the course of the legal processes, victims’ voices were heard and a considerable amount of documents were dug up, showing the involvement of the Japanese Army.

The Japanese Government undertook two investigations in the “comfort women” issue, and in 1993 Kono, the then chief cabinet secretary, admitted the historicity of forced sexual service and offered apologies and remorse. At the conference on human rights of the UN in 1993 and at the World Women’s Conference in 1995 in Beijing the issue of “comfort women” was one of the foci. The Human Rights Committee of the UN issued advice to the Japanese Government. These developments took place against the background of the surging democratisation and women’s liberation movement in Asia.

Against this background the Japanese Government published its position that the issue of compensation is already settled in the light of the San Francisco Peace Treaty and subsequent bilateral agreements. However, in 1995 it set up Asian Women’s Fund, collecting donations from Japanese citizens and providing some fund for running expenses. It began to pay victims ‘atonement money’. But many victims demanded an official compensation from the Japanese Government and declined the money. The governments of South Korea and Taiwan took steps against this fund.

In 1993 the Dutch Government conducted an investigation into the issue of “comfort women”. Whereas its general stance was similar to that taken by the Japanese Government, namely the question of compensation is already settled, a non-governmental organisation, PICN, negotiated with the Japanese Government and accepted about 3 million Yen for medical and welfare projects.

In Indonesia the Legal Support Association and the Heiho Association called on non-governmental bodies, investigated on victimised “comfort women” and had them registered, but the Indonesian Government itself did not conduct any investigation or lend support to these efforts. It took the view that the issue of compensation is already settled with the Japanese Government, saw no need of individual compensation, and would not listen to complaints by victims. The fund from the Asian Women’s Fund was added to the budget for building senior citizens’ homes.

So the Asian Women’s Fund, without having fully achieved its aims, was disbanded in 2007. No real resolution of the issue nor reconciliation has resulted.

3. Backlash in Japan and the Women’s International War Crimes Tribunal 2000

When the issue of “comfort women” surfaced early in 1990’s and it also attracted global attention, Japan witnessed violent backlash over the issue in the second half of 1990’s. In 1997 all history textbooks in use at middle-schools inserted a mention of “comfort women”. Politicians, intellectuals, and right-wing organisations who deny the historicity of “comfort women” began to attack textbook publishers. As a result, textbooks published in 2012 make no mention of “comfort women”.

This trend is also reflected in the fact that after 1997 the media began to  reduce its coverage of the “comfort women” issue. After 1997 the NHK did mention the issue in daily news coverage, but did not make any investigative programme touching on the “comfort women” issue. Thus began a 15-year period of silence. As a result of attacks and criticism by right-wing organisations public museums and galleries would not venture exhibitions touching on the “comfort women” issue. It became impossible to organise meetings and exhibitions on the issue at public venues. In this way the “comfort women” issue became a taboo in various forums in Japan.

reduce its coverage of the “comfort women” issue. After 1997 the NHK did mention the issue in daily news coverage, but did not make any investigative programme touching on the “comfort women” issue. Thus began a 15-year period of silence. As a result of attacks and criticism by right-wing organisations public museums and galleries would not venture exhibitions touching on the “comfort women” issue. It became impossible to organise meetings and exhibitions on the issue at public venues. In this way the “comfort women” issue became a taboo in various forums in Japan.

One lawsuit after another demanding the Japanese Government an apology and compensation was thrown out at Japanese courts. Efforts began to be made to find what Japanese women could do for disappointed victims. In 1998, Ms Yayori Matsui, an ex-journalist working for Asahi-shinmbun and active for the cause of women’s liberation, proposed that an international civil court be convened in Tokyo in order to deal with the issue of sexual slavery in the Japanese Army. The proposal found an enthusiastic welcome both among Japanese women and among victims and their supporters. They immediately started on a search for judges, a court constitution was drafted, and texts of indictment began to be written in various countries. The women’s court met in December 2000. There were present 64 victims from 8 countries and 1,300 visitors from 30 countries round the world every day. The victims shared their horrifying experiences, and there arose a loud applause when Japanese veterans spoke of their own deeds of rape and exploitation at comfort stations. Voluminous documentary evidences presented by judges from various countries and arguments by specialists on the responsibility of the Emperor and the Japanese Government added to the tension and rigour of the proceedings. On December 12, when the verdict of “Guilty” was pronounced on the Emperor and the Japanese Government was declared to bear national responsibility, the female victims were overjoyed, saying “Justice has not abandoned us.”

Some 200 reporters of 95 overseas media channels reported this outcome as the top news of the day, but the response shown by the Japanese media was rather modest. Moreover, the NHK, which had been chasing this women’s court for quite some time, broadcast a strange, incongruous programme. The organisers of the court launched a lawsuit against the NHK. In 2005 the NHK staff who was involved in the production of the programme revealed that the then cabinet chief secretary, Shinzo Abe, interfered out of a political motive. The lawsuit that ensued lasted seven years. At the Tokyo District High Court the plaintiff won the case, but at the Supreme Court, lost the case, and the NHK denies the politically motivated interference by Abe. This rare case of political interference in a programme and exposure of the media’s submission to it became an unusual piece of the postwar history of broadcasting in Japan.

Shinzo Abe, an MP who rose to the premiership in 2006, kept attacking textbook publishers, serving as the administrative secretary of a group calling itself “Association of young MPs concerned about the future of Japan and history education.” Premier Abe asserted that there is no evidence of “comfort women”, forced prostitution, which led to critical resolutions by parliaments in the USA and Europe. Under the second Abe premiership he continued the same assertion and interfered in appointments of NHK personnel. Not only the NHK, but also the mainline Japanese media tended to go along with the current Government and practise self-censorship when it comes to the “comfort women” issue. At the end of 2015 the Governments of Japan and South Korea reached an agreement towards the resolution of this issue. The Japanese Government and the media sighed a sigh of relief, thinking that the issue is settled for now. But the surviving Korean victims and the national public opinion were highly critical, saying that a political agreement that has not taken victims into account is no solution. The public opinion on this issue in the two countries is diametrically opposed, and reconciliation between them is not in sight.

4. Activities in support of “comfort women” across Japan and what can women of guilty Japan do here?

After 1991, when Ms Kim Haksun came out, the “comfort women” issue led to a number of lawsuits, there started in Japan activities in support of these court cases. Because my father was stationed in Hang Zhou, China, I began to support the legal battle of the Chinese plaintiffs together with colleagues who belonged to “Facts-finding group on Shan Si Sheng.” I have not forgotten the shock I received on hearing in 1991 or 1992 personal stories told by Korean victims. The scenes described were so cruel and atrocious. The hall was chock-full with many people standing and even the entrance hall was full. One could hear lots of people sobbing. We were amazed at the  courage of those victims in sharing these painful memories. At the same time we became ashamed that we had been ignorant up to then of those atrocities committed by our Japanese soldiers, and felt very, very sorry for those victims. I began to think about what we could do as Japanese. Though I was at the time involved in projects on cases of HIV-tainted blood scandal, I vowed to investigate, research on the “comfort women” issue, and inform as many Japanese as possible of this issue. At the end of 1996 I had produced eight ETV programmes for the NHK, all dealing with the “comfort women” issue.

courage of those victims in sharing these painful memories. At the same time we became ashamed that we had been ignorant up to then of those atrocities committed by our Japanese soldiers, and felt very, very sorry for those victims. I began to think about what we could do as Japanese. Though I was at the time involved in projects on cases of HIV-tainted blood scandal, I vowed to investigate, research on the “comfort women” issue, and inform as many Japanese as possible of this issue. At the end of 1996 I had produced eight ETV programmes for the NHK, all dealing with the “comfort women” issue.

But after 1997 when right-wing groups began to assail middle-school history textbooks which contained descriptions of the “comfort women” issue, my repeated proposal to make a programme on the issue was turned down. This coincides with the above-mentioned 15-year period of silence on this issue. I began to worry about the prospect of these women getting too old to leave any records for the future. While still working with the NHK, I launched a private video project and began to make video records. For the women’s court in 2002 I was a member of the executive committee, and had the proceedings broadcast worldwide via the internet. After the NHK had telecast the programme revised through the political interference, I immediately produced a programme entitled “Shattering the history of silence,” and became one of the plaintiffs suing the NHK.

Following the premature death in 2002 of Ms Yayori Matsui, who had proposed Women’s Court and worked hard for its success, and following in her footsteps, we founded the WAM on “comfort women”, the only museum of its kind in Japan, and it opened its doors to the public in August 2005. We continued simultaneously to visit surviving victims in $ China at least twice a year and provide them with some medical support, whom we had supported for their lawsuit at a Japanese court, and heard their stories and collected relevant data and records. Also after the decease of the last victim we maintain contact with their children. After the panel exhibition at WAM on Chinese victims we had the text translated into Chinese, and in 2009 we began to hold a related panel exhibition in Chinese universities and museums. In the Red Army Memorial Museum in Wu Siang and the Anti-Japanese Resistance Movement Museum in Beijing we had such a panel exhibition held six times. In Taichen in Shan Si Sheng a ten-year permanent exhibition has started.

I have maintained contact with and supported Chinese victims over twenty  years. I venture to think that they and I are reconciled with one another. Initially our Chinese victims thought that we had been sent by Japanese municipalities or businesses. Later they realised that we represented a grass-roots citizens’ group of volunteers, and our mutual warm friendship and understanding across the national frontiers began to deepen. When we visited Ms Wan Aifa (83), the chief plaintiff from $ in her hospital bed, she encouraged us by saying: “You need to put a strong pressure on the Japanese Government for a resolution of this issue,” “Let’s change the Japanese Government,” “Please keep on fighting, never give up. If you give up, you would be looked down.” Have been informed that her death was not far away, we struggled hard to hold our tears back. Holding her hands, we said to her: “We are always with you, Miss Wan. We shall keep on till we win. You keep watching, please.” Nine days later she passed away.

years. I venture to think that they and I are reconciled with one another. Initially our Chinese victims thought that we had been sent by Japanese municipalities or businesses. Later they realised that we represented a grass-roots citizens’ group of volunteers, and our mutual warm friendship and understanding across the national frontiers began to deepen. When we visited Ms Wan Aifa (83), the chief plaintiff from $ in her hospital bed, she encouraged us by saying: “You need to put a strong pressure on the Japanese Government for a resolution of this issue,” “Let’s change the Japanese Government,” “Please keep on fighting, never give up. If you give up, you would be looked down.” Have been informed that her death was not far away, we struggled hard to hold our tears back. Holding her hands, we said to her: “We are always with you, Miss Wan. We shall keep on till we win. You keep watching, please.” Nine days later she passed away.

5. In conclusion: what does reconciliation mean to me?

If perpetrators and victims, the two nations represented by them share the same target towards a resolution of the problem, talk to each other, and act together, they may be able to achieve mutual reconciliation. I have been fortunate in that through my involvement in the Women’s Court and WAM I have been able to come into contact with victims not only of China, but also of other countries, and build up a relationship of honest communication. But this is only about a relationship between us and them, victimised individuals. As long as the Japanese Government persists in taking a negative stance in relation to the “comfort women” issue, the reconciliation at the national level the victims are after has yet to be achieved. It is incumbent on us native Japanese to strive to change the stance of our government.

In May 2015 some Japanese groups supporting “comfort women”, in cooperation with eight Asian non-governmental organisations attempted to have the “voice of “comfort women” under the Japanese Army” registered as a UNESCO world heritage site, but the Japanese Government has kept up efforts in public and behind the scenes in order to sabotage this attempt. As a result the registration is not yet complete. Japanese right-wing media have been persistent in their abuse and attacks, and WAM received from one of such groups a letter twice, threatening a bomb attack. We are determined not to be scared by these “assassins of memories,” but to pass on records and memories of “comfort women” to the next generations, and to preserve them in history.

I believe that we ought not to forget what was achieved by the Women’s Court in 2000, but to take our responsibility for Japan’s war guilt, and to prevent Japan from becoming a nation yet again wanting to launch a war. This is what is expected of us, the post-war generation of Japan, and this is a way leading to reconciliation.

Thank you for your attention.

(Translated by T. Muraoka)

6. Verzoening onderzocht ⎮Toyomi Asano

War, Myself, and Reconciliation – Toyomi Asano (Waseda University)

Born in Fukushima, I have come to understand how Fukushima has been intertwined with Japanese national history, related not only to the nuclear power station but to such historical events as wars, dismantling of empire, repatriation and Japanese post-war resettlement. Now, I am proceeding a project of developing a new reconciliation studies, which is supposed to function as a tool to pacificate a conflict between national emotions, which seems to have been formulated along with such national events of wars and higher economic development.

In my preposition, national emotions are inclined to combine international incidents with local and vivid memories, in such a way as how ‘our’ familiar and ancestors in local level worked in such and such international situations. Recently in the process of globalization with human exchange and global media, more and more local memories are inclined to be focused as a source to sustain a national memory, which explains where we are in the world.

In order to formulate the local memory. The method of oral history is now actively adopted by researchers. As I will show you my own ancestor’s story, I came to be connected to Japanese national narratives, which once gave me a power as a researcher and meaning in my own private life.

Thinking of reconciliation, we must proceed to the next step that is to consider how several different national narratives could be connected with each other, which could be regarded as an entrance to the reconciliation between nations. But before going there, it should be jointly understood and shared how each nation itself is being imagined in our own inspiration. I wish that a kind of new reconciling relation between nations could be imagined somehow in the same way each nation itself is being imagined in our mind.

Before going to the story, I want to underscore the difference in the way each nation has been built between East Asia and Europe. In East Asia “National identity” was both rapidly and politically built because we tried to catch up with the Western civilization by forming a powerful and full-fledged nation-state that could be recognized as a sovereign state on an equal basis, while European nation-state building process forwarded in its own natural dynamics for over 3 to 4 hundred years.

However, the artificially-made quick process of Japanese nation building was intertwined not only with wars between the powers which were related with such peripheral regions as Ryukyu, Taiwan and Korea, but with Japanese colonial rules over Asian peoples who lived there. Nation building was intertwined with Empire building, which triggered another Asian’s nationalism of anti-colonial rule in 20th century. For example, comfort women issues are regarded as sex-slave issues for Korean women but Japanese comfort women also did exist, who derived from 19 century Japanese prostitutes in Western settlements in East Asia.

National memory has been incorporated into each nation’s identity which is intertwined with contemporary domestic political system. For example, when looking back on the aftermath of World War II, the German people in Europe have focused on the value of the concept of “democracy” and human rights. This was because Germany as a nation, once allowed the Nazis to take power and build up a one-party dictatorship through a constitutional process with legal suppression of human rights. On the other hand, Japanese public mourning after the second World War has been inclined to focus upon the value of “peace”, because under the pretext of emergency and war, democracy was suppressed, which made Japanese to regard peace more important lesson than democracy. This could be also explained from the fact that most of Japanese people shared an experience of air raids and atomic bombs. Even though Japanese soldiers had committed atrocities in the war, which entailed violation of human rights in occupied areas, such events seems to have very weak influence upon national identity to protect human rights.

It is relatively easy to envisage the wars experienced by “my people,” especially from the perspective of my people being on the victims’ side. In fact, Japanese memory about the wars tends to focus on the value of peace. But it does not necessarily lead to reconciliation between peoples. Our desire for reconciliation could be regarded as a challenge to such a defensive character of national memory, by situating each form of nationalism in the historic context of East Asia, where the concept of a nation itself was artificially introduced by a state in the process of ‘civilization’

Asian national identity had been artificially reinvented by a newly installed modern state in the short time span of a few generations. Paradoxically, that would be a key to detach ourselves first from each of our own national memory as victims and face each other to remember the common past, which could be shared with universal values, though each national memories would not disappear but reconcile together.

In this short presentation, I would like to express my own memories toward my grandparents, as an example of explaining the way nation is imagined in my mind and how people in Asia was quickly embraced to a nation in the process of modernization and wars. Because I was born in a rural area, left behind the higher development of economy of post-war Japan, I was fortunately surrounded by a rich environment full of historical memories.

“Memories of the Russia -Japanese War, heard from my Grandfather”

Modern Japan fought two major wars in the 20th century, the Russo-Japanese War in 1904 and the Asia-Pacific war in 1937, which amalgamated into the Second World War. These two wars were related to each other as the first, bearing the cause of the last one, which was in fact evoked with Japanese prerogative in Manchuria taken in the first Russo-Japanese war. And this process occurred during the same time when nation building of Japan was proceeding, which would be shown in my family history who were involved in these two wars.

My grandfather was born in January 1897. When he was 8 years old in 1905 at the end of the summer vacation of elementary school, he welcomed Japanese soldiers on the railway, being escorted by a teacher to stand along the local train. The soldiers welcomed by my grandfather were from Karafuto along the Tohoku Main railway Line.

This interview was done when I was a graduate student in the department of International Relations Studies in Tokyo University around 1990, when I was beginning to research how Japan’s modern nation building overlapped the road to the colonial empire. My grandfather, already around 95 years old, then touched my heart by connecting me personally to Japanese and international history. The soldiers on the train were imaginable for me because I spent my childhood in the same scenery even though there was a double track railway. While I myself was escorted by teachers on excursions to the same space in 1970’s, my grandfather had been escorted in the beginning of 20th century by a teacher to go to the same train track to wave Japanese flags of the Rising Sun. In the interview with my grandfather I could imagine his childhood days as if it had happened to me at the same time. The soldiers returning from Karafuto on the train reacted to the children on the ground by throwing red and white rice cakes to the children.

“Memories of WWII, heard from my Grandmother”

Next, I would like to introduce my grandmother who was born in 1905, as one of the first generation of rural girls who could read and write. I remember a small trip with my grandmother when I was taken to the nearby city Fukushima when I was still an elementary school boy. Trying to go back to the platform of the station after all shopping finished, I found my grandmother stopping in front of the entrance of the platform, seeing a board of train schedule. She said she was so thankful that she could read the characters written on the signboard showing train schedules. She was viewing them from top to bottom. I myself had learned how to write letters from this grandmother before I entered a kindergarten.

My grandmother affectionately reminisced her lost son “Yukio,” who passed away in 1944 during WW2. My uncle, Yukio, born in 1922, was recruited in 1943 and mobilized for the Leyte Battle in the Philippines. However, in mid-April 1944, on his way to the Philippines, his transport ship “Teiamaru” was sunken by an American submarine and disappeared in the Bassi Strait between Taiwan and the Philippines. My grandmother’s memory seemed to be lingering over the last night when she saw him. Just before the departure of the ship to the south, Yukio was allowed to return home and appeared suddenly at home at 3:00 AM after a long walk perhaps from the big city of Fukushima. During my grandmother’s preparation to cook special rice for him because he must go back to the station before noon, he cut his nails and hair as substitutes for his body in case of his death in the battles, saying he could not be back again.

Memory and reconciliation

These stories were documented as a graduate student, so they can still be presented here as my memory. However, when I was asked to come to speak in the Netherlands, these stories had almost vanished from my consciousness. In retrospect, it is a valuable record for considering how my grandparent’s narratives were internalized in my own childhood when my identity was in the formation process.

It would be possible to say that “the memory” undergoes a reformation process in order for human beings to maintain the balance of the mind and to continue living as survivors. The central memory of my grandmother lays in the last day of the separation from her son. This might also show how a victim’s perspective of the national history is stronger than the perpetrator’s perspective.

On the other hand, the story of the Russo-Japanese War I heard from my grandfather seems to be linked to the introduction of a modern civilizational device, that is railway. My grandfather’s earliest memories seem to be connected to technology and civilization as perceived by Japanese rural children. It is significant that my grandfather always valued the fields beside the railway, and often walked along the railway, which, as a location, may have also overlapped with his own grandfather, in short my great-great grandfather’s memories, who contributed to the railway construction by supporting to gather land for the railway company as a counselor of the village’s township.

Nation seems to be inclined to connect local memories with international context, forming them into a national story. It has made me think again that the modern age is truly made up of individuals who are always even unconsciously searching for meanings of life by nurturing emotional memory as a subject for inspiring each life.

As an extension of these experiences, I came to consider how to understand the function of memory to inspire people, and how to reconcile them meaningfully for the future. Since I myself have become a researcher, I have begun to think about the national memories recorded by each nation and the possibility of reconciliation among people. When I first entered the university, I faced foreign students who were raised hearing family’s memories of colonial days.

Through personal encounters with foreign students from Taiwan and Korea, I was deeply moved by the level of contrast in the nature of colonial memories by these two peoples. For Korean students in general, colonial memories are memories of “the times when it was better not to have existed”. On the other hand, for students from Taiwan, it is a memory of “the very era when the Taiwanese were born as a nation”. It may be possible to say that Chinese students who regard Japan as a rival or as the winner in modernization could be in the middle between Koreans and Taiwanese. Because the colonizer and the colonized all belong to Asia and Japan tried to assimilate them during colonial days, the reconciliation seems the more difficult.

In any case, the emotions of the peoples around Japan cannot be expressed without the existence of Japan itself. That would be similar to Japanese emotions that could not be expressed without the existence of the center of “civilization,” as “Western Europe” and “the Great Powers.” The atrocities involving Dutch civilians during the World War II could be an outburst of the Japanese with complex psychologies toward the West and the Powers.

Emotions seem to be difficult to control. Collective emotions are much more difficult than private one.

The first step is to make emotional local memory stabilized, by connecting it with a global history. Such a global history/narrative would contribute to a constructive dialogue between peoples about emotional subjects.

(2) But the second step is also indispensable, particularly in this global age, which is how to differentiate our own emotions toward others through the prism of three concepts of emotions, such as “empathy” (sympathy), compassion (mercy), and fraternity (French: fraternité, in the UK: fraternity) , as illustrated in the theory of Prof. Ute Frevert. (Emotions in History: Lost and Found)

Being mindful and aware of these two above methods of dialogue, and the realization that these two methods are the minimum required for the process of reconciliation to begin. “Empathy” could be an emotion used in an equal relation. Compassion is an emotion arising out of a sense of superiority, while “fraternity” is directed to members of the same group or nation as a subject of identity.

One difficulty of the realization of reconciliation is that people are not freed from the tendency of these complex feelings directed to a group like a nation or a race rather than an individual as citizen. This inclination is explained in detail in a famous scholar, Benedict Anderson’s “Imagined Community” that a nation can be collectively “imagined” against other nations.

Particularly in wars, human emotions toward other groups are systematically mobilized for conveying wars. The third emotion of “fraternity” toward the same national people would be heightened during wars by a sense of national destiny and superiority that includes the act of discrimination against other people. It can be said that “empathy” and even “compassion” toward other nations would be controlled psychologically by national consciousness itself. Either strong insulation or pity that derives from this period would be internalized even to children and would be transferred to the next generation.

In conclusion to this specific paper, personally, I strongly hope through the new level of historical studies being developed by international co-operation that more young people can find their own national emotions which exist inside ourselves as an object of inter-connected global history and discuss the process of the formation of their upper generation’s emotions, finally results to connect each national emotion in a broader picture of a global history as I have tried in this speech even tentatively. Thank you so much.

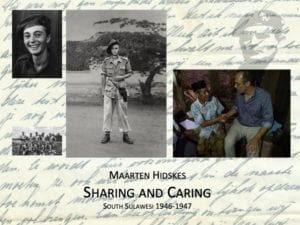

7. Sharing and Caring⎮Maarten Hidskes

Dear ladies and gentlemen,

It is a great honor for me to be here and at the request of the Foundation Dialogue NJI to share my experiences in Indonesia with you. I thank the NJI for the opportunity to contribute something to the important theme of today.

My subject is about a war in which the compartmentalization between “us” and “them” was at its high. This polar thinking has been part of the socialization of the colony and resulted in a great deal of violence in a period of five years, followed by decades of silence.

From the 90s onward, in the Netherlands a situation arose where people with different views spoke against each other instead of with each other. Discussions broke down on the definition of words, such as war crimes and on the inability to recognize oneself in the view of the other. It was also claimed that Dutch people knew what the Indonesian thoughts about the war at the time were. Some serious oral history projects did not go beyond the offices of research institutes.

However, the colonial past holds lessons which could give a positive spin on the future. Certainly, with the current knowledge of today it should be possible to look very deep into our own past.

However, the colonial past holds lessons which could give a positive spin on the future. Certainly, with the current knowledge of today it should be possible to look very deep into our own past.

I would like to share my experience in Indonesia with you. In September 2018, I traveled 10,000 kilometers throughout the country, speaking with around 1200 history students, a number of relatives and eyewitnesses of colonial violence, dozens of teachers and some history committees. These encounters contained a form of reconciliation, even though the journey was not explicitly designed as a reconciliation project. Indeed, reconciliation has not even been pronounced as such, but was, at least for me, tangible in another way: acceptance, interest, an openness on the Indonesian side, and a relaxed attitude on my part.

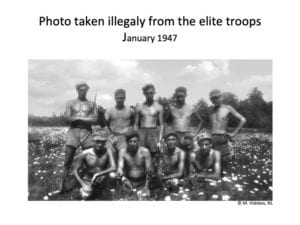

My book, ‘At home nobody believes me’, is a deliberate confrontation with a  painful episode in my father’s life. The book is a reflection of my research into his voluntary participation in executions carried out by colonial elite troops at the Indonesian island of Sulawesi in 1946. In colonial history, military violence on Sulawesi, later referred to as the South Celebes affair, remains an open nerve.

painful episode in my father’s life. The book is a reflection of my research into his voluntary participation in executions carried out by colonial elite troops at the Indonesian island of Sulawesi in 1946. In colonial history, military violence on Sulawesi, later referred to as the South Celebes affair, remains an open nerve.

Since my father passed away, I had to search for eyewitnesses to find answers to the question why he and his small group traveled to Sulawesi with the best intentions to already after a few days, execute people beyond any legal framework.

The book is a personal quest for the motives and impressions of one single soldier. I carried out this search without judgement or defence of my father and sincere to my own feelings.

The South Celebes affair occurred relatively early in the five years of hard battle between the Netherlands and its former colony. For twelve weeks, from December 1946 onward, military actions took place on Celebes. These actions consisted of the summary execution of persons whose guilt was not clearly established and carried out without the backing of any legal framework or having established a fair punishment for their actions.

My father’s small elite unit probably executed 600 people, while a much  larger group perished by force of the army and police. Altogether, three- up to five thousand people have probably died. After Indonesia’s independence in 1950, there was no social debate in the Netherlands for the first 20 years, neither was there after that. All the facts are known, but there was no debate. Paul Bijl, professor of literary theory, considered the processing of colonial history from a medical point of view and and interpreted lack of debate and speech as a neurological disorder of national aphasia (i)

larger group perished by force of the army and police. Altogether, three- up to five thousand people have probably died. After Indonesia’s independence in 1950, there was no social debate in the Netherlands for the first 20 years, neither was there after that. All the facts are known, but there was no debate. Paul Bijl, professor of literary theory, considered the processing of colonial history from a medical point of view and and interpreted lack of debate and speech as a neurological disorder of national aphasia (i)

We knew something happened, but we did not get the concepts and images to the right speech center. What had happened on the individual level within the South Celebes affair no one knew. The old commands were untraceable, and if they were approached by chance they hardly provided insight in their real inner thoughts. More than ordinary soldiers they were bound by their self-agreed elite codes. The outside world only asked closed questions, also full of assumptions that almost always boiled down to guilt and punishment.

The perpetrators, the eyewitnesses themselves, had never been interviewed. Upon return in Holland, they were considered heros by half of the population, and by the other half as war criminal.

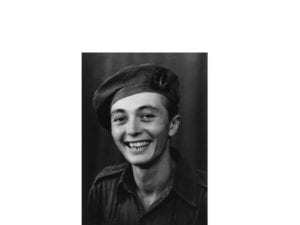

After their time in Indonesia, most ex-commandos tried to close this part of their lives and focused on founding a family and building a life. The discussion was so twisted and one-sided that not after long they didn’t feel the need to participate in any debate. My father was one of these 123 men and after his death in 1992, I carried out an investigation into his motives and actions during this period.

I looked not only into his personal psychology, but also the society from which he originated and the environment in which he functioned are being investigated by me. I show the effect of factors such as self-coercion, group coercion, external encouragement and the dynamics of an isolated group with an unlimited mandate of violence. The book combines many sources, including conversations with old commands, letters from my father, interviews with eyewitnesses, intelligence reports as well as national and private archives.

My non-fiction book is about the self-chosen – intimate – confrontation between father and son. The book shows me as an investigating son in the twilight zone between truth and love. After a painful tangible struggle, I finally choose both. The book shows my final acceptance of the inconvenience: he was the man I loved but also the man who lived twenty years before my birth in an unimaginable world and committed unimaginable acts.

(i)Paul Bijl: “Colonial memory and forgetting in the Netherlands and Indonesia”. In: Luttikhuis, Bart (ed.): Colonial Counterinsurgency and mass violence, p. 261-281. Routledge, 2014.

Reception in the Netherlands

When you write such a personal story, you carry it close to your heart until the day of publication. Releasing it is scary, because soon everyone will have an opinion about it. I was pretty conscious about that. However, the book was well received in the Netherlands and rather frequently discussed. Not just the reviews were positive, with a single neutral discussion at the lower end, also from the many live radio interviews and the personal reactions of readers appreciation for the accessibility of the story became apparent. The chosen perspective of father and son proved to be an excellent form of narration for readers and a good starting point for a conversation.

Reception in Indonesia

The Indonesian translation appeared in the summer of 2018. The need for s translation in Indonesia was obvious: the violence in Sulawesi and the leader, Captain Raymond Westerling, take in the history about the origin of the republic of Indonesia an important – and also sensitive place. It was obvious that the book could not just be dumped on the Indonesian market. So for the appropriate introduction of the book, the Indonesian publisher and I started a series of 14 discussions at universities in Sulawesi, Java and Kalimantan. The starting point was sharing history, or sharing different perspectives on history in order to gain better insight into that history.

Seventy two years after my father set foot on Indonesian soil as a soldier, I set foot on same ground. His military pocketbook was replaced by a weblog and a notepad. His bullets had been replaced by words, a keyboard and a camera. The book was the starting point for conversation and exchange.

My father shot Indonesians. How do you open the conversation about this? My starting points of the presentations and the conversations were:

- Keys are: acceptance, connection, sharing, up for discussion and visibility.

- Information and interpretation are important; feelings and emotions as well.

- The joint history is jointly owned. There is not one truth, there are many perspectives. 4. I only speak from myself and on behalf of myself. I’m not going to think for others, speak or conclude. My limited perspective leaves room for the other.

- I openly state that I am aware that I am trying to be neutral but probably am not.

- I make myself vulnerable and hope that the other will do the same.

- I am aware of the effect of the words that I use. I avoid words that can have a polarizing or politicizing effect.

- Implicitly, I invite Indonesians to express their perspectives, insights and feelings.

I tried to draw a horizon for myself of the reactions and emotions which I had to take into account. I had no idea what to expect. There were no examples. To what extent does this history still play a role in Indonesia? In to what extent could I expect emotions and pain? Would people accept that I came to explain my father’s story? How did I transfer my own consciousness on my colored vision? Would anyone blame me?

Prior to the first discussion I was pretty nervous, to say the least. Which will have been just as much on the Indonesian side: the son of a man who volunteered to shoot down Indonesians was here to explain how it went. I estimated there was a considerable risk that someone would stand up in the room and say: are you trying to get approval for your father’s war crimes by creating understanding for his actions? I tried to prepare for such a conceivable moment. Such a response would have been unpleasant, yet I can explain very well that it would have been not right. Pointing out my good intentions, I could have explained all that. But that would not have been the appropriate approach. I was therefore set to respect such reaction, and to attribute great value to it. I wanted to put myself into the emotions and world of that person.