Dialoog NJI Symposia samen met NIOD

Friday 3 June 2016, 13.00-17.00 at NIOD, Herengracht 380, Amsterdam

The ‘Stichting Dialoog Nederland-Japan-Indonesië’ in collaboration with the NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust, and Genocide Studies (https://niod.nl) organized a symposium on the occasion of the visit of members of the ‘POW Research Network Japan’ to the Netherlands.

This symposium was co-organised with the NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust, and Genocide Studies (https://niod.nl) and was made possible by NIOD and by a contribution from the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sports (VWS).

NIOD Symposia video impression

Program

Welcome by Eveline Buchheim, NIOD

-

- Introduction to the POW Research Network by Yoshiko Tamura, POW Research Network

- POW camps in Japan during the Pacific War by Taeko Sasamoto, POW Research Network

- Netherlands East Indies and Australian POWs in Hainan island by Fuyuko Nishisato, POW Research Network Japan

- Dutch civilian internees in Japan by Mayumi Komiya, POW Research Network

- Personal recollections from POWs in the NIOD collection by Eveline Buchheim, NIOD

- Discussion led by Peter Keppy, NIOD

- Final remarks by Yukari Tangena-Suzuki, ‘Stichting Dialoog Nederland-Japan-Indonesië’

1. History of POW Research Network Japan and What We Aim for | Yoshiko Tamura POW Research Network Japan

Inauguration of POW Research Network Japan

Even now people in Japan don’t speak much about war history. Not many people know there were prisoners of war camps in their neighborhood and what they were doing there. All was hidden and they were forbidden to get in touch with those foreign soldiers taken to Japan and forced to work. So each of us had been a lonely researcher for years just until March 2002. We launched our organization to work together for investigating the history of prisoners of war (POWs), civilian internees and war criminal trials as well as to promote a process of exchange with former POWs, internees and their families. We voluntarily got together on POW issues without any funds or any relationship with specific political or religious associations.

Starting members were only twenty but our network gradually attracted more people, eventually the number has now reached seventy in total. Our members include people from all walks of life from university students to retirees, up to age over ninety, including school teachers, journalists, and Japanese veterans. Some are foreign residents and some are Japanese living overseas.

Careers of members

In Japan, with teachers’ having very little knowledge on the POW issue, students rarely learn about it at school. The question may arise why each of us is so interested in this issue. For example, Taeko Sasamoto and Yoshiko Tamura live very close to the Commonwealth War Cemetery in Yokohama. Both of us were strongly interested in this cemetery with very little information on these young foreign solders interred there.

Fuyuko Nishisato, as a journalist, while investigating the Biological Warfare Unit 731, got to know the POW camp in Mukden, China, and started to study the possibility of human experiments. Mayumi Komiya happened to aware that the first principal of her school was in an internment camp during the war, and began studying internees in Japan. One of the two co-founders of our organization, Prof. Aiko Utsumi is an expert on POW issues in Japan, especially on the War Crime Trials. Toru Fukubayashi, the other co-founder, studied and located all the POW camps in Japan. He is also the expert on B-29 cases. There is a colleague who is interested in the so-called ‘hell ships’ which transported POWs to Japan.

The Aim of Our Activities

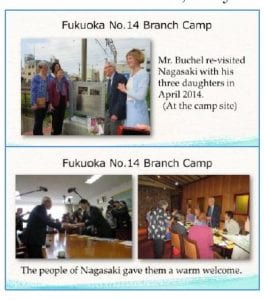

All the members of our organization live not only in Tokyo and Yokohama, but also in various other parts of Japan and overseas. So through our mailing list on the internet, we usually exchange ideas and information. Once a year, we engage in fieldwork to a former camp site with colleagues nearby. In 2014, we went to Nagasaki on the visit of Mr. Willy Buchel van Steenbergen and his daughters. He was a POW of No.14 Camp there. It was a good chance for us to learn about this camp walking around the site with him. Sometimes we go abroad to study. We have been to Taiwan, Singapore, Thailand and some other countries to see camp sites and to meet local people. In 2006 we had a joint seminar at the Australia National University with scholars, researchers and former POWs.

In 2004, we finally completed the list of deceased POWs in Japan, who are interred in the Commonwealth War Cemetery in Yokohama. As soon as the list was put up on our website, we were amazed with incredibly increased number of inquiries.

In 2009, at the request of the National Archives of the Netherlands, we worked on the translation of POW personnel cards into English. They were the cards made by the Imperial Japanese Army to record each POW’s movements after his captivity, and then were submitted to Holland after the war.

As the only organization in Japan that specializes on the POW issue, we seem to be recognized in Japan and overseas, and inquiries are increasing from former POWs and their families as well as other authorities, the mass media, academics and ordinary citizens. We are very pleased to help them and eventually contribute to make the POW history known to Japan and to the world.

Moments of Reconciliations

From time to time, ex-POWs and their families pay personal visits to Japan. With the cooperation of members who live close to the location of their former POW camp sites, we try to show them around the area and take them to the Commonwealth War Cemetery in Yokohama.

Our Ministry of Foreign Affairs has had a project to invite former POWs from the United Kingdom as well as ex-POWs and internees from the Netherlands. Those children whose biological fathers were Japanese are also invited to Japan. Some of them met their fathers and families. In 2010, they started another project to invite ex-POWs from Australia and the United States. We collaborate with the Ministry to provide information of former camps to give ex-POWs a chance to visit these camp sites and hold gatherings with Japanese citizens. Through such visits and meetings with Japanese people, we discovered that many of them who held a grudge against us for years, started to open themselves to us and even to express sympathy to the sufferings of the Japanese in those days.

One good example we’d like to introduce are monuments unveiled on 13 September 2015. There was a POW Camp called Fukuoka No. 2 in Koyagi Island, Nagasaki. Many of the POWs were Dutch and they were forced to work at a shipyard nearby. Until the day of their return to their homelands, 73 men passed away due to various causes like pneumonia and beriberi, or by tragic accidents. People in Nagasaki, mostly Atomic Bomb survivors and their descendants became aware of another side of their history. They realized they were not only sufferers but also assailants, when they met former POWs and their families. Atomic Bomb victims especially worked hard to build a monument for the deceased POWs at the camp site. Our organization supported them wholeheartedly and provided research materials and coordination with people from overseas.

Eventually eighteen Dutch and ten British people came for this unveiling ceremony as well as representatives of the concerned Embassies, the Governor and Mayor of Nagasaki, Nagasaki citizens and some of us from our organization. Among these people from the Netherlands there was a ninety-year-old former Dutch POW Henk Kleijn. Furthermore four Americans attended. They were the sons and grandchildren of the only survivor of the B-29. His plane crashed onto the mountain on 4 September 1945, on route to the dropping of a relief supply operation to Koyagi camp. Thirteen airmen were killed instantly. This tragic accident was detailed in a diary by a British POW. The sons and family had a dramatic meeting with their father’s rescuers the day following the ceremony. More news about this topic is on this report recently published.

To overcome hatred and to keep peace together

Many POWs went home with physical and mental scars, which turned into suffering in their later lives. It made their spouses distressed, and this suffering has been often handed down to their children, too. There is a lot our government can do and there are some more that we citizens can do on a grassroots level. There are some who still have nightmares and flash backs which have never gone away, but have kept them suffering for years. What we do as members of POW RNJ is, firstly, to investigate this history, secondly, to handover this record to the young generation. It is not based only in Japan. Meeting people abroad and working together makes us learn more. And thirdly, frequent communication brings us understanding and friendship, we believe. In this way we wish if we could build a Bridge for Peace for our better future through our activities.

2. POW Camps in Japan during the Pacific War | Taeko SASAMOTO

Good afternoon, ladies and gentlemen. Thank you for that kind introduction.

Good afternoon, ladies and gentlemen. Thank you for that kind introduction.

I am Taeko SASAMOTO, the Secretary of the POW Research Network Japan. For the past 20 years, I have been conducting research on the POW Camps in Japan

during the Pacific War.

At the early stage of the war, Japan took about 350,000 Allied soldiers prisoner. Of those, since the Asian POWs in occupied Southeast Asia were released after pledging allegiance to Japan, about 140,000 Caucasian prisoners were actually interned as POWs. They were forced to engage in the construction of railways, roads, and airfields in the Japanese occupied areas. As you already know, their living conditions were severe.

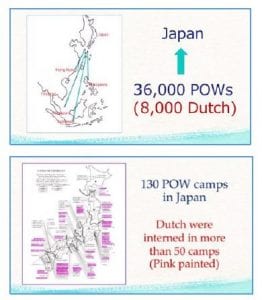

In those days, since adult males were sent to the front lines, Japan was suffering an acute shortage of manpower at home. In order to fill the vacancies, about 36,000 POWs were transported to the Japanese homeland. Of those, about 8,000 were Dutch.

In those days, since adult males were sent to the front lines, Japan was suffering an acute shortage of manpower at home. In order to fill the vacancies, about 36,000 POWs were transported to the Japanese homeland. Of those, about 8,000 were Dutch.

There were 130 POW Camps established at various locations in the country, where the prisoners were forced to work at mines, shipyards, factories, and harbors. Their life in Japan was also very severe, resulting in the death of about 3,500 of them by the end of the war. Of those, roughly 900 were Dutch.

Counting a Camp that had only one Dutch interned, Dutch POWs were held in more than 50 different Camps in the country. Some arrived in Japan from Java via Singapore, while others came after the completion of the Thailand-Burma Railway.

In contrast to the American, British, Australian and Canadian POWs, the Dutch POWs seemed somewhat different in status because there were many of Indonesian – and therefore, Asian – origin among them. As a result, some Japanese felt familiarity with them. A former camp guard said, “The Indonesian Dutch are gentle and mild. I often invited them to my house, asked them to help with gardening, and then shared the

harvests with them in return for their work.”

I’d like to talk now about some of the Camps in which the Dutch POWs were interned, and some episodes associated with them:

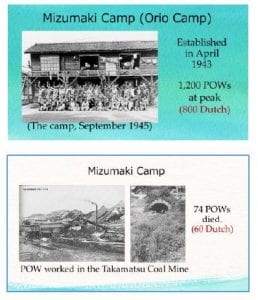

First, about Mizumaki Camp, located in Kyushu Island: This camp was also called “Orio Camp”. It opened in April 1943, with roughly 1,200 POWs interned, the majority of whom (more than 800) were Dutch.

Most of them worked in the coal mines, engaged in digging and extracting coal in the deep underground, and carrying it to the outside. As you can imagine, it was very hard work, but they were sent underground relentlessly, even if they got sick. Safety precautions were insufficient, resulting in many casualties from cave-in accidents. The living conditions of this camp were, as in other camps, severe and hard. Food and medical supplies were meager, and the POWs suffered violence from the Japanese. Consequently, 74 POWs died by the end of the war. Sixty were Dutch.

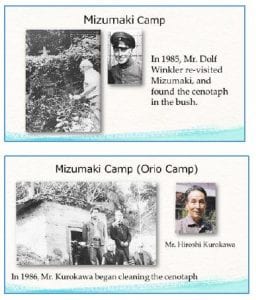

Immediately after the war, in order to give a good impression to the Occupation Forces, the Mining Company erected a small building with a cross on top for housing the ashes of these deceased POWs. However, no ashes were ever enshrined in this building. The ashes of the American and Dutch POWs were repatriated to their respective countries, and those of the British and Australian POWs were transferred to the Commonwealth War Cemetery in Yokohama. The cenotaph was left as it was, and entered a state of ruin.

In 1985, a former Dutch POW, Mr. Dolf Winkler, re-visited Mizumaki, and found the cenotaph buried in bush. He made an appeal, on behalf of his comrades who died a regrettable death far from home, asking that the cenotaph be put in good condition. Hearing this, Mr. Hiroshi Kurokawa, a local resident who recalled having seen the poor POWs in his childhood, organized “Cenotaph: The Committee to Promote Peace and Culture” in response to Winker’s desire, and began cleaning it.

In 1985, a former Dutch POW, Mr. Dolf Winkler, re-visited Mizumaki, and found the cenotaph buried in bush. He made an appeal, on behalf of his comrades who died a regrettable death far from home, asking that the cenotaph be put in good condition. Hearing this, Mr. Hiroshi Kurokawa, a local resident who recalled having seen the poor POWs in his childhood, organized “Cenotaph: The Committee to Promote Peace and Culture” in response to Winker’s desire, and began cleaning it.

In 1987, a bronze plate inscribed with the names of Dutch POWs who died in Mizumaki

was placed on the cenotaph. In 1989, similar plates with the names of all Dutch POWs who died in Japan were added, and tulips sent from school children in the Netherlands were planted around it.

School children and older students in Mizumaki began cleaning up the cenotaph, and learning the history of the POW Camp in their town. Furthermore, the students of Mizumaki and those of Noordoostpolder, where Winkler lived, began a student-exchange program, visiting each other’s towns for a home-stay.

When the Dutch war victims are invited to Japan by the Japanese Government every year, they invariably visit Mizumaki, and enjoy getting together with the local people.

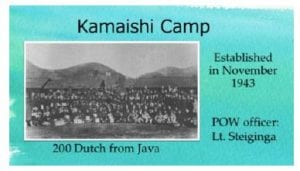

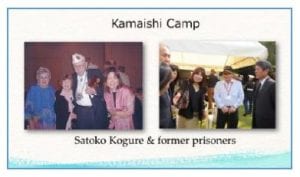

Next, I’ll tell about Kamaishi Camp, on Japan’s northeast coast. This is a story about a former POW Camp commandant tried as a war criminal, and his granddaughter. This camp was established in November 1943, and interned 200 Dutch POWs from Java. The senior Dutch officer was First Lieutenant Steiginga.

Next, I’ll tell about Kamaishi Camp, on Japan’s northeast coast. This is a story about a former POW Camp commandant tried as a war criminal, and his granddaughter. This camp was established in November 1943, and interned 200 Dutch POWs from Java. The senior Dutch officer was First Lieutenant Steiginga.

The POWs worked at the steel blast furnace, and were also engaged in loading ore and limestone, operating lathes, welding, and repairing machinery. In less than 3 months from their arrival, 16 POWs died. The cause of death was mostly pneumonia. They were weakened when they arrived,

The POWs worked at the steel blast furnace, and were also engaged in loading ore and limestone, operating lathes, welding, and repairing machinery. In less than 3 months from their arrival, 16 POWs died. The cause of death was mostly pneumonia. They were weakened when they arrived,

and had difficulty adjusting to the cold weather in northern Japan after their transport from tropical Java. Under the first Japanese Camp Commandant, food and medication were insufficient for their recovery.

The second Camp Commandant, Second Lieutenant Makoto Inaki, attempted to let the POWs have as much nourishing food as possible, and strictly forbade his subordinates to use violence on the POWs. In consequence, they gradually regained their health, and their recorded weight was the highest of all POW camps in northern Japan. Lieutenant Steiginga gave praise, saying “Kamaishi is the best camp in Japan.”

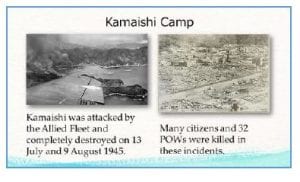

As 1945 began, air raids against large cities in Japan intensified, and in May, about  200 POWs were evacuated from the Tokyo-Yokohama metropolitan area to Kamaishi. However, on 14 July and 9 August, U.S. and British Task Forces appeared off Kamaishi, and battle ships rained their 16-inch guns’ shells on the city. Kamaishi was completely destroyed, and many of its citizens were killed. The POW Camp located near the seashore was also totally destroyed, and 32 POWs were killed.

200 POWs were evacuated from the Tokyo-Yokohama metropolitan area to Kamaishi. However, on 14 July and 9 August, U.S. and British Task Forces appeared off Kamaishi, and battle ships rained their 16-inch guns’ shells on the city. Kamaishi was completely destroyed, and many of its citizens were killed. The POW Camp located near the seashore was also totally destroyed, and 32 POWs were killed.

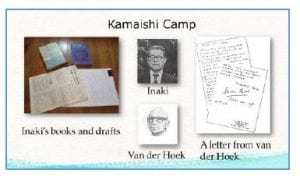

After the war, Commandant Inaki was tried as a war criminal and sentenced to 7 years of hard labor on a charge of mistreatment of the POWs. While serving his sentence, he was subject to pent-up anger, believing that he had tried to treat the POWs as fairly as he could. After his release from prison, he became a newspaper reporter, and wrote books on his unhappy experiences.

One day, 30 years after the war, a letter from Mr. van der Hoek, a former Dutch POW, was delivered to Kamaishi City Office, and redirected to Inaki. It read, “We were well treated at Kamaishi, and the local people were kind to us.” For Inaki, it had the effect of a divine revelation, and relieved him from long years of mental depression. For roughly 10 years thereafter, Inaki and van der Hoek corresponded with each other until their deaths.

One day, 30 years after the war, a letter from Mr. van der Hoek, a former Dutch POW, was delivered to Kamaishi City Office, and redirected to Inaki. It read, “We were well treated at Kamaishi, and the local people were kind to us.” For Inaki, it had the effect of a divine revelation, and relieved him from long years of mental depression. For roughly 10 years thereafter, Inaki and van der Hoek corresponded with each other until their deaths.

Ms. Satoko Kogure, Inaki’s granddaughter, was quite shocked when she read her grandfather’s book in her high school days. He did his best for the POWs. Nonetheless, he was tried as a war criminal. Why? Weren’t the Allies in violation of the Geneva Convention, shelling Kamaishi indiscriminately? What on earth was the war for? In order to study about those matters, she enrolled in a university’s Faculty of Law, and began researching the Kamaishi Camp.

When she contacted me through a third person, I asked her to join our Network, and visited America with her to attend a General Assembly of former POWs. She read books on the experiences the POWs had undergone, and by empathizing with them, she realized that it was an undeniable fact that Japan had mistreated the Allied prisoners. She also realized that not only the POWs, but her grandfather, was a victim of the war in a sense, and she determined that there should be no more war in the future. Satoko now works as an editor for Newsweek magazine, and writes about issues of war and peace. A few years ago, she visited the bereaved family of van der Hoek in the Netherlands, as well as a former US POW she came to know. She was warmly welcomed.

When she contacted me through a third person, I asked her to join our Network, and visited America with her to attend a General Assembly of former POWs. She read books on the experiences the POWs had undergone, and by empathizing with them, she realized that it was an undeniable fact that Japan had mistreated the Allied prisoners. She also realized that not only the POWs, but her grandfather, was a victim of the war in a sense, and she determined that there should be no more war in the future. Satoko now works as an editor for Newsweek magazine, and writes about issues of war and peace. A few years ago, she visited the bereaved family of van der Hoek in the Netherlands, as well as a former US POW she came to know. She was warmly welcomed.

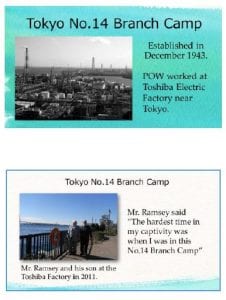

The next Camp is Tokyo No. 14 Branch Camp, located in the industrial area near Tokyo. It opened toward the end of December 1943, with a total of about 200 Dutch, British, Australian, and American POWs, who were interned as workers at Toshiba electric factory.

The next Camp is Tokyo No. 14 Branch Camp, located in the industrial area near Tokyo. It opened toward the end of December 1943, with a total of about 200 Dutch, British, Australian, and American POWs, who were interned as workers at Toshiba electric factory.

The life in this camp was indescribably severe. Mr. Ramsey, a former Australian POW, survived the construction of the notorious Thailand-Burma Railway and the sinking of a hell ship on his way to Japan. When he visited Japan a few years ago, he said the hardest time in his captivity was at this Tokyo No. 14 Branch Camp.

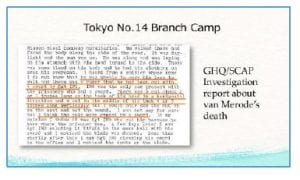

The camp’s location changed 4 times during the war. Of the 4 times, two were caused by the camp’s being burned to the ground by air raids. In the first air raid, in April 1945, van Merode, a Dutch POW, was killed. According to the death record prepared by the Japanese Military, the cause of his death was “killed by bombing.” However, postwar investigation by the Allied Forces revealed that a Japanese Army sergeant killed him with a sword in the bustle and confusion of an air raid. As van Merode was disabled, he might have been a drag on others during evacuation.

The camp’s location changed 4 times during the war. Of the 4 times, two were caused by the camp’s being burned to the ground by air raids. In the first air raid, in April 1945, van Merode, a Dutch POW, was killed. According to the death record prepared by the Japanese Military, the cause of his death was “killed by bombing.” However, postwar investigation by the Allied Forces revealed that a Japanese Army sergeant killed him with a sword in the bustle and confusion of an air raid. As van Merode was disabled, he might have been a drag on others during evacuation.

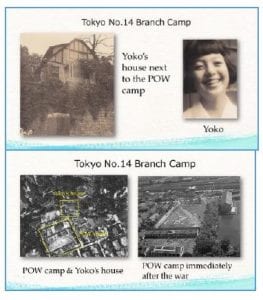

The third Camp was built within the enclosure of the Toshiba factory. But it was also burned down by an air raid on 13 July 1945, and as many as 29 POWs were killed. Of these, 22 were Dutch.

The fourth Camp was built in the middle of a residential area toward the end of July. In the house next to the Camp, there lived a 16-year old girl by the name of Yoko. Every day she practiced the piano, as she wanted to enroll in a music school. One day, as she chanced to look outside through a window of her room, she saw a POW on the roof, listening to her play. From the following day on, the number of POWs on the roof increased to 2, 3, 4 … and finally about to 20 altogether. Soon, the war was over, and B-29s flew over the Camp, dropping relief supplies. Then on 30 August, the day came for the POWs to go home. About 20 POWs visited Yoko’s house with bags on their shoulders. “Thank you for playing the piano. Our spiritual thirst was very much relieved.” So saying, they handed bags to Yoko. There were canned goods, cigarettes, sugar, chocolate bars, and so on; precious gifts the Japanese could not afford in those days. After enjoying the tea that Yoko’s parents served, the POWs rode on a bus that came to pick them up, and were gone waving their hands.

The fourth Camp was built in the middle of a residential area toward the end of July. In the house next to the Camp, there lived a 16-year old girl by the name of Yoko. Every day she practiced the piano, as she wanted to enroll in a music school. One day, as she chanced to look outside through a window of her room, she saw a POW on the roof, listening to her play. From the following day on, the number of POWs on the roof increased to 2, 3, 4 … and finally about to 20 altogether. Soon, the war was over, and B-29s flew over the Camp, dropping relief supplies. Then on 30 August, the day came for the POWs to go home. About 20 POWs visited Yoko’s house with bags on their shoulders. “Thank you for playing the piano. Our spiritual thirst was very much relieved.” So saying, they handed bags to Yoko. There were canned goods, cigarettes, sugar, chocolate bars, and so on; precious gifts the Japanese could not afford in those days. After enjoying the tea that Yoko’s parents served, the POWs rode on a bus that came to pick them up, and were gone waving their hands.

On Yoko’s notebook, some POWs wrote down their names and addresses. Three years ago, Yoko asked a newspaper in England to search for their whereabouts. Two of the POWs’ bereaved families were found. She has been in correspondence with one of the families since. Today, in Yoko’s house, the piano she played to relieve the POWs’ spiritual thirst still keeps a sweet timbre.

On Yoko’s notebook, some POWs wrote down their names and addresses. Three years ago, Yoko asked a newspaper in England to search for their whereabouts. Two of the POWs’ bereaved families were found. She has been in correspondence with one of the families since. Today, in Yoko’s house, the piano she played to relieve the POWs’ spiritual thirst still keeps a sweet timbre.

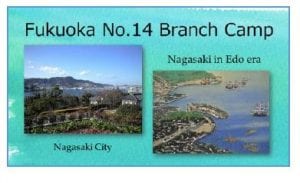

Nagasaki is located on the island of Kyushu, and had close ties with the Netherlands. During the period of national isolation between the 17th and 19th centuries, for the Japanese, the Netherlands was the only country permitted to trade thru Dejima in Nagasaki. So we were connected, thru Nagasaki, to the Netherlands, and then to the world in those days.

During the war, there were 2 POW camps in Nagasaki. One was Fukuoka No. 2 Branch Camp, in the suburbs of the city, and another was Fukuoka No. 14 Branch Camp, located  near ground zero of the atomic blast. The Dutch POWs had a majority in both camps.

near ground zero of the atomic blast. The Dutch POWs had a majority in both camps.

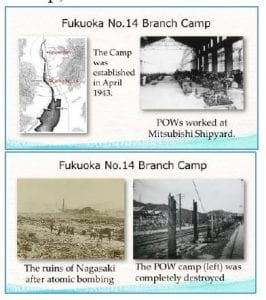

No. 14 Branch Camp was opened in April 1943, and had 500 POWs interned at its peak. They worked at Mitsubishi Shipyard, and over 100 of them died from illness and in accidents.

In addition, on 9 August 1945, 8 more POWs were killed by the atomic bombing. Of those, 7 were Dutch.

Those who barely survived the disaster must have suffered various aftereffects from radiation exposure after the war. The Japanese Government issued the “Medical treatment note for A-bomb victims” to some survivors. However, since the surviving POWs lived abroad, they could not receive any substantial medical support.

In 2014, a resident of Waalre, Mr. Willy Buchel, was issued the Medical treatment note.

In 2014, a resident of Waalre, Mr. Willy Buchel, was issued the Medical treatment note.

Taking advantage of this opportunity, he visited Nagasaki with his three daughters.

The people of Nagasaki gave them a big warm welcome, with full support from our Network.

After receiving the note, Buchel took legal proceedings against the Japanese Government for his right to seek compensation denied him because he was a resident abroad. Mr. Buchel did not seek this

for monetary reasons, but to improve the rights of all A-bomb victims living abroad.

In March this year, the two parties reached a settlement, and the compensation was paid to him. This was the very first time that compensation was paid to a former POW: an epochal event. He decided to donate the money to the pacifist groups in Japan, and kindly added our Network to his list as one of them. We were deeply moved and appreciative of his kindness, considering the fact that he has undergone the indescribable hardships of POW and A-bomb victim.

As for Fukuoka No. 2 Branch Camp, Mrs. Tamura has already talked about it, so I will now conclude my speech.

As you can easily imagine, each of the 130 POW camps that once existed in Japan has its own hidden truths of history. I would very much like to unearth them, and hand them down to the next generation. Thank you all for your time, and I hope that you better understand the wartime POW camps in Japan.

You can download the presentation here.

3. Netherlands East Indies and Australian POWs in Hainan island by Fuyuko Nishisato, POW Research Network Japan

You can download her presentations slide-1 | slide-2

4. The Dutch civilians who were interned on Japan’s main island during WWII | Mayumi Komiya: POW Research Network Japan

(Introduction)

Hello everyone. My name is Mayumi Komiya. I’m a member of POW Research Network Japan. Thank you for giving me this occasion to talk to you. I have been doing research on the foreign civilians who were interned as enemies in Japan during WWII. I’d like to tell you today about the Dutch people who were interned on the main island of Japan.

It is commonly known that around 100,000 Dutch civilians were interned by the Japanese in Java during WWII. The number was huge, so I suppose those internees and their families probably still hate the terrible treatment. And those painful experiences must be vividly remembered in the Netherlands. However, it might not be common knowledge that there were some Dutch people who were interned in the camps on the main island of Japan, suffering similar painful experiences.

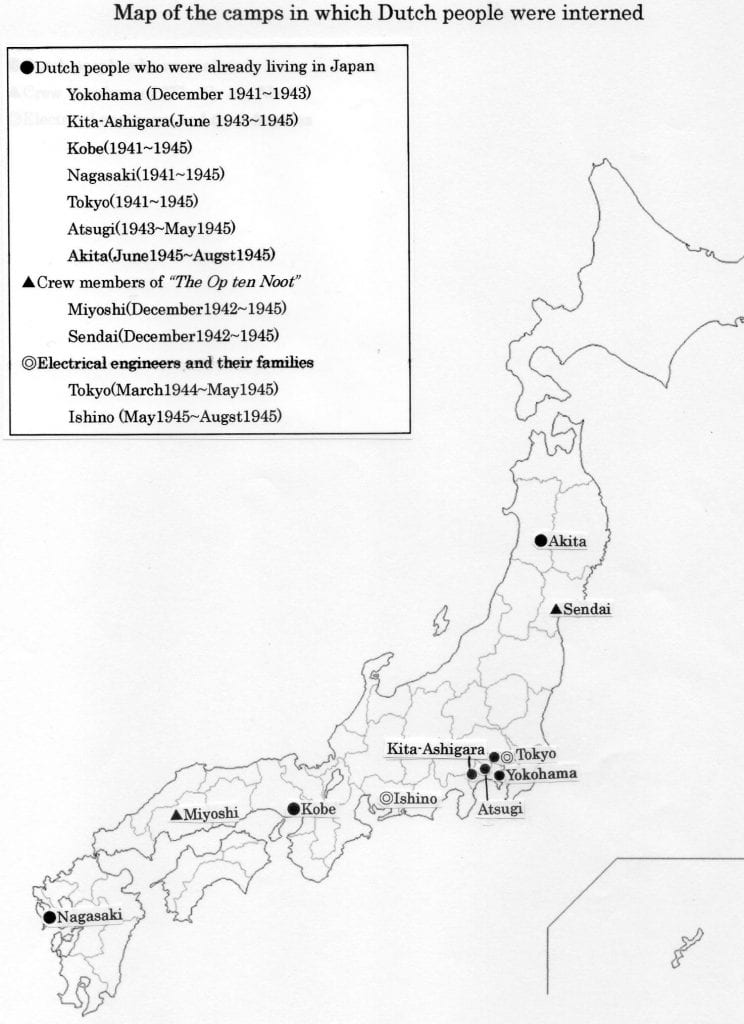

The Dutch internees in Japan proper are divided into three groups. The first group was Dutch people who had already been living in Japan since the prewar days. The second group was the crew members of a Dutch hospital ship, which had been captured by the Japanese. The third group was the Dutch electrical engineers and their families who were captured in Java and transferred to Japan. I will talk about each group in detail, like when and where they were interned, and how their internment life was.

(1.Dutch people who had already been living in Japan)

When the war started, Dutch people who had already been living in Japan were interned first. Let me talk a little about those Dutch civilians who had lived in Japan.

In Japan, since the 17th century, the Tokugawa government pursued the Isolation Policy with the intention of protecting the country from invasion by foreign powers. The Netherlands was the only country which was allowed to trade with Japan among the Western countries. So after reopening the country to the world, some Dutch people worked as teachers employed by the Meiji Government, or as engineers, as academics, and so on. They contributed to Japanese modernization and development.

However, Japan started to invade part of China in the 1930s. The international relations between Japan and other countries became bad, in particular the US and the UK. Under the threat of war, some of the Dutch people who were living in Japan returned to their country or left for other countries. But some remained in Japan for various reasons. At the beginning of December 1941, just before the outbreak of the Pacific War, there were 109 Dutch people in Japan, which was much smaller than 1044 Americans and 690 English. The total number of the people whose nationality belonged to one of the Allied Nations was 2138, with 5% being Dutch people. (note1)

On December 8, 1941, the Japanese military made a surprise attack on the US Forces at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, and the Pacific War started. The US and the UK declared war against Japan immediately, and the Netherlands did the same on December 10. Japan and the Netherlands became enemies.

Because of the outbreak of the war, a lot of foreign residents in Japan were considered to be enemy aliens. Thus the internment of foreign people in Japan began. The Ministry of Home Affairs of Japan had a policy, that male adults would be interned in the camps, and female adults, children and the elderly would be confined at home under the vigilant watch of the police. As of the end of December 1941, the total number of those internees was 342, including 23 Dutch people.

They were interned where they lived; therefore, eight Dutch people were in Kobe city Hyogo prefecture, five were in Tokyo, four were in Nagasaki, three were in Kanagawa, one each was in Aomori, Shiga, and Kumamoto respectively. (note2)

The number of Allied Nations’ residents and internees in Japan, on December 1941

| Allied Nations’ residents in Japan | The number of residents | The number of internees |

|---|---|---|

| American | 1044 | 93 |

| English | 690 | 106 |

| Ernst Handel | Roland Mendel | Austria |

| Canadian | 188 | 67 |

| Dutch | 109 | 23 |

| Australian | 41 | 1 |

| Belgian | 38 | 16 |

| Norwegian | 19 | 1 |

| Greek | 9 | 14 |

| Other nationalities 18 | ||

| total | 2138 | 342 |

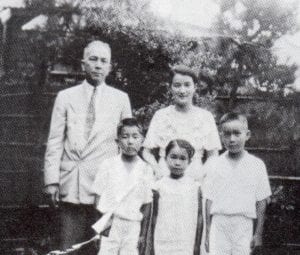

One of the internees in Kanagawa was Mr. Herman Donker-Curtius. His grandfather was Jan Hendrik Donker Curtius. The grandfather was famous as the last director of the trading post in Dejima, Nagasaki, and signed the first trade treaty between the Netherlands and Japan in 1855.

Before the war, Mr. Herman Donker-Curtius owned a dairy product factory in Kanagawa, but when the war started he was immediately captured by the special secret service police and was interned. His internment camp was the former jockey quarters of the horse race course in Yokohama City. His internment was such a shock for him because he really loved Japan. (note3)

Besides the civilian internment, seven Dutch people were arrested under the suspicion of espionage. And eighteen Dutch diplomats were confined to their embassies or consular offices. Around sixty female adults, children and elderly people were confined at home. They were separated from their husbands or fathers and lived in strong anxiety.

In June 1942, an exchange ship left Japan for Europe, on which those foreigners who were considered enemies were returned to their countries. Boarding the ship “Tatsuta Maru,” 41 Dutch people returned to the Netherlands, including 14 male adults who had been interned. However, some people decided to remain, because they couldn’t leave their property or Japanese families. Mr. Herman Donker-Curtius was one of them.

In September 1942, the internment policy regarding females was changed. The internment of foreign women, who had been working as teachers, missionaries or nuns, started. So two Dutch nuns were put into the Tokyo Camp. After that in December 1943, internment policy was changed more strictly. To follow that, women, children, and the elderly who were living in Yokohama were interned in a camp which was newly opened in Atsugi city Kanagawa Prefecture. Three elderly Dutch women were held there, two of them being the elder sisters of Mr. Donker-Curtius.

At the beginning of the war, the meals in the camps were not so bad. Then from around 1943, when the Japanese started losing battles in the Pacific, the lack of food and goods became serious problems. Camp food became scarce and shabby. Besides, air raids of the cities in Japan started. As a result, the Yokohama camp in which Mr. Donker-Curtius had been held, was moved to Kita-Ashigara village (present Minami-Ashigara city). It was in the mountains at the foot of Mt. Hakone. Also the Atsugi camp, where the sisters of Mr. Donker-Curtius were, was moved to Akita Prefecture.

Due to the lack of food and medical care, many internees were getting sick and some people even died. Before the end of the war, there were five deaths among the 53 internees of Kita-Ashigara village camp. There were six deaths in the 33 internees of the original Atsugi Camp later in Akita.

It was fortunate that no Dutch internees died, but it was certain that even if they could survive, their internment life was very hard. On August 15, 1945 at the end of the war, there were around 60 Dutch people living in Japan, including 11 internees.

(2.The crew members of a Dutch hospital ship )

The second group was 79 crew members of a Dutch hospital ship named “The Op ten Noort”. (note4) On February 27, 1942, in the Battle of the Java Sea, the Allied navies suffered a disastrous defeat at the hand of the Imperial Japanese Navy. “The Op ten Noort” was captured by the Japanese in that battle, so the crew members surrendered. In December 1942, that hospital ship was forced to sail to Japan and arrived at Yokohama port. Then 42 Dutch professionals were sent to Miyoshi City in Hiroshima prefecture. They consisted of 18 officers including Captain Tuizinga, seven doctors and 17 nurses. Two Indonesian engine drivers were also sent to Miyoshi with the Dutch.

On the other hand 35 Indonesian sailors from the ship were sent to Sendai City in Miyagi prefecture, as well.

In Miyoshi City their internment camp was originally a kindergarten building which was established by a Canadian missionary. The camp wasn’t guarded by the Japanese army but rather by the Japanese police, and there was no forced labor or abuse. However, the internees were worried about Japanese coldness because of their summer clothes. Lack of heating in the rooms and lack of food tormented them. According to a record of the captain, the average weight decreased 26 kilograms for a man, and 10.6 kilograms for a woman, by the end of the war.

Meanwhile in Sendai City, Indonesian sailors were interned in the camp which was the building of Mototerakoji Catholic Church. One Indonesian sailor died from illness there. On July 10, 1945 that Church was burnt down in an air raid by American bombers. Indonesians were evacuated to another church in terror. It was lucky that no Indonesians died in the attack.

After the war Dutch and Indonesian crews left Japan on September 14, 1945. They returned to Batavia via Manila.

(3. Dutch electrical engineers and their families)

The third group was Dutch electrical engineers and their families. The number was 22, including women and children. Mrs. Annie Lels, one of the internees wrote her experiences in her diary titled “Diary by Annie Lels-Visser Deportation to Japan” (“Dagboek van Annie Lels-Visser Deportate naar Japan” in Dutch). (note5)

In The National Radio Laboratory of the Netherlands in Bundung Java, electrical engineers who had high education were working. Dr. Einthoven was a managing director of the Laboratory. In March, 1942, when the Japanese military invaded Java, the electrical engineers destroyed the Laboratory and surrendered. The Japanese Army made them work to carry on the Radiotelegraphy Station briefly. Then in November 1943, five electrical engineers including Dr. Einthoven were sent to Japan with their families of six women and eleven children. They departed from Batavia to Japan in January 1944, and after a long voyage via Singapore, they arrived in Japan. Then they were sent to Tokyo and interned in the building which was the former legation of Chile. The electrical engineers were made to work for the laboratory of Sumitomo Communication Industry in Ikuta, Kawasaki City. It was an order by the Japanese Army. The Army tried to use them to invent the radar system. They commuted to Ikuta by train every day. In February 1945, the flu prevailed, and Dr. Einthoven, the leader of the group caught it and died of pneumonia.

Tokyo City was often air-raided since March 1945. Therefore the group was made to evacuate to Ishino village, Aichi prefecture. Their camp was a temple called Kotaku-ji. They coexisted in the temple hall. There were no chairs or no beds in it.

They were not given normal food but millet porridge with vegetables. Sometimes flour was added instead of millet, so it tasted like glue. The Dutch people ate snakes and wild grass which they could find to supplement their nutrition. According to the “Diary” written by Annie Lels, Ms.Pauline Lels, who was a daughter of Annie, twelve years old said with tears “Oh Mother, I am so miserable. We are given too little food here, I‘m always hungry, my body is trembling.” Even though mothers were making some handmade toys to cheer up their children and gathering some berries, fruits and sweet potatoes to celebrate their children’s birthdays.

After the end of the war, they could move to a hotel in Nagoya City by the charge of the Swedish Embassy.

On September 4, they started from Nagoya to head for Australia via Manila.

(Conclusion)

Overall, around 130 Dutch people were interned in Japan proper during WWII. Before the end of the war, one Indonesian sailor in the second group and one Dutch engineer in the third group died in the camps. The number of the deaths in Japan is only two, which is much less than that in Java. Even so, I have a feeling of deep remorse for the severe treatment of those Dutch civilians in Japan.

I think the experience of Dutch people in the third group was very unique. The wisdom and strength of mothers who had protected their children should be admired. I could learn their experience from “Diary by Annie Lels-Visser Deportation to Japan” which was translated into Japanese by a Japanese lady. I’ve heard that the Diary wasn’t published, but stored up in this NIOD until now. I really respect NIOD which is working to hold those valuable records and to open them for the public.

Thank you.

Note:

1 Home Affairs “Gaiji Keisatsu Gaikyo ( Roughly Report of Foreign Police) 1941”

Reprinted edition, Ryukei-shosya 1980

2 Home Affairs “Gaiji Geppoh (Monthly Report on Foreign Affairs) December 1941”

Reprinted edition, Huji-Syuppan 1994

3 Akiyoshi Sato ‘Kazoku no Shozo (Portrait of the famly) 12’ “Yokohama” Kanagawa Newspaper Company 2008 spring

4 Kunitaka Mikami “Kaigun byouinsen wa naze shizumeraretaka (Why the navy hospital ship was sank)” Huyoh Shobou Press 2001

5 Annie Lels-Visser “Dagboek van Annie Lels-Visser Deportate naar Japan (Diary by Annie Lels-Visser Deportation to Japan)” private edition by A. P. Greeven-Lels 1998

Keiko Toda translated into Japanese 2004

5. Personal recollections from POWs in the NIOD collection by Eveline Buchheim, NIOD

No text available

6. Discussion led by Peter Keppy, NIOD

No text available

7. Final remarks by Yukari Tangena-Suzuki, ‘Stichting Dialoog Nederland-Japan-Indonesië’

Good evening Ladies and Gentelemen.

I am Yukari Tangena-Suzuki, the chair of Stichting Dialogue Netherlands-Japan-Indonesia. Thank you so much for joining us this evening!

It was our great pleasure and honour that we could introduce to you the five excellent researchers this evening.

From the moment I learned that some persons from the Japanese POW Research Network would be prepared to visit the Netherlands, I very much wished to organize a symposium. As some of you already know the Stichting Dialoog NJI is the organization to seek for reconciliation among people of three countries to aim for a better relationship between each other. With that in mind I strongly felt it is my duty to introduce the POW Research Network to the Netherlands, since they have been helping so many ex-POW’s and their families.

I believe reconciliation creates a continuous wish for further improvements. It is not only a one-off thing, but reconciliation makes you want to work on a better world. Therefore, I hope that both Dutch and Japanese researchers use this opportunity to work together more and more so that we understand each-other better and so prevent a repetition of the mistakes of the past.

This symposium would not have been possible without Eveliene and Kippy of the NIOD. Thank you very much for your kind support. You really made this symposium a very meaningful one. I am also very grateful that you gave us an opportunity to use this wonderful space. I think this is also a beautiful reconciliation gesture to hand out to the Japanese researchers.

I am very grateful that this really happened this evening and hopefully many of you will also join our program in Utrecht tomorrow.

Last but not least, could you please give a big applause to the four ladies who came all the way from Japan to share their studies? We would like to sell a report and book about POW Camp Fukuoka No.2. Please visit the desk if you are interested.

Well, downstairs there are some beverages so let us toast our glasses for our continuous friendship. I hope you will go home with good feelings.

Thank you very much!